Like chicken tikka, the sarod is a sublime product of the Moghul influence in India. Simon Broughton learns the secrets of the instrument from its leading contemporary virtuoso, Amjad Ali Khan

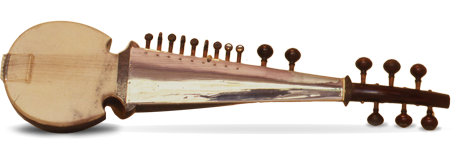

first encountered it at the BBC Proms in the Royal Albert Hall in 1994 when a sarod recital at 2am was the finale of a late night concert of Indian music. It was a revelation –Amjad Ali Khan, distinguished and silver-haired, leading a refined journey into musical equivalents of the Taj Mahal, Moghul palaces and hilltop fortresses. Elegance and refinement, supported by a cohesive structure and deep foundations.The sarod is much smaller than the sitar. It sits comfortably in the player’s lap and is leaner and cleaner in sound, without that predominant jangling of sympathetic strings. The sarod has resonant sympathetic strings, but they are fewer and far less prominent in the soundscape. Still, it’s no less demanding to play. “People like to talk about the king or prince of sarod, but actually I’m the slave of sarod,” laughs Amjad Ali Khan acknowledging how hard it is to master, yet also confident that no one is likely to outshine him. “I am devoted to it and I always want to try and find out what it wants to say.”

Amjad Ali Khan, born in Gwalior (Madhya Pradesh) in 1945, is the sixth-generation sarod player in his family and his ancestors have developed and shaped the instrument over several hundred years. “You could say it’s my family instrument”, he says with justifiable pride. “Whoever is playing the sarod today learned directly or indirectly from my forefathers.”

The instrument speaks eloquently of the close connections between India and Afghanistan and the Persian world. Architecture, food and music are amongst the great hybrids born of the Islamic invasion of northern India through Afghanistan. The sound of the sarod as we know it today is distinctly Indian in character, but it links to the sinewy, muscular style of the Afghan rabab - a wooden Central Asian lute, covered with skin. For Amjad Ali Khan it’s the tone quality that’s the attraction: “The skin makes the sound very human - it’s not wooden. It has flexibility, sensitivity and depth.” The sound of the sarod is dominated by the singing, vocal tone of its melodic strings. Many instrumentalists -including violinists, clarinettists, sarangi and sitar players - like to compare the sound of their instruments to the human voice. And sarod players are no exception. “I actually spend as much time singing as playing,” admits Amjad Ali Khan and through his father he learned about applying the vocal traditions of dhrupad and khayal to his instrument.

“I am singing through my instrument,” he says. One of the principal modifications of the sarod from the Afghan rabab is its long metal fingerboard, which allows swooping melismatic slides between the melody notes. This is something you can’t do on fretted instruments. This is a big advantage of the sarod over the sitar”, he explains. “On the sitar you have to pull the string sideways to create the slides. And you can’t pull that far - not more than 3 or 4 notes. But on the sarod you can slide over 7 notes or more, skating up the fingerboard.” As well as this lyrical, vocal style, Amjad Ali Khan is renowned for his fast staccato passages up and down the instrument - something he has made very much his own. This is the latest addition to a long tradition of sarod playing and Amjad Ali Kahn’s two sons, Amaan Ali Khan and Ayaan Ali Bangash, are now taking it forward to the next generation. As with the Griots of West Africa, lineage and family are hugely important in Indian music. You wonder what would have happened had one of Amjad Ali Khan’s sons said they were more interested in the electronic keyboard, or accountancy!

Some sarods, like the Afghan rabab, are made from mulberry wood, but most are made, like the sitar, from teak. According to Amjad Ali Khan, teak gives a fuller, richer sound. The front of the wooden belly is covered with goat skin. The best place to get goat skins is Calcutta and that’s where most of the sarod makers are based, including Hemendra Chandra Sen, of Hemen & Sons, who is around 80 years old and the most important sarod maker in India. “In Bengal,” explains Amjad Ali Khan, “there is a strong cult of Kali worship and there are lots of sacrifices to her. There are lots of goat skins in Calcutta and that’s why you find most of the tabla makers there too. This is the character of India and its history. A Hindu woman wears a beautiful Sari made by Muslims in Varanasi. I myself am a Muslim, but I play an instrument made in Calcutta by a Hindu. We all have different religions, but we depend on each other. The history of India is like that.”It was Amjad Ali Khan’s forefathers that effected the most important development in the instrument and replaced the wooden, fretted neck of the rabab with a smooth polished-steel fingerboard which permits the characteristic slides (or meend) which are used extensively at the beginning of a composition to establish the raga. Just as a tabla player will always have his bottle of talcum powder to sprinkle on his drums, Amjad Ali Khan has a small, decorated box of palm oil to help his left had slide effortlessly around the fingerboard. The rabab’s gut strings have also been replaced by steel ones – piano strings in fact – which give a much more ringing, and singing tone. There are just four strings used for playing the melody, two drone strings and two chikari strings (raised drone strings which are used to punctuate the melodic phrases with rhythmic accompaniment). Amjad Ali Khan uses 11 sympathetic strings (tuned to the notes of the raga), although other players use more which increases the reverberant effect. The four melody strings are generally tuned (from the top) doh, fa, doh, mi. The lowest string is made from bronze and has a deep, powerful sound, “full of passion”.

The strings are not plucked with the fingers, but with a java or coconut-shell plectrum. “This plectrum can be a hammer or a feather,” says Amjad Ali Khan. “You can play very loud, or give it just a feather touch, skimming gently across the strings.” Actually, the range of colours that a player like Amjad Ali Khan can get out of the instrument is quite incredible and is certainly why it’s found such an important role in classical Indian instrumental music.

Like many musicians who play an instrument that’s been ‘elevated’ from folk to classical status, Amjad Ali Khan can talk quite dismissively of the rabab. “It’s not a very expressive instrument,” he says, “and quite limited.” Using the soft tips of his fingers, he imitates the duller, more gutty sound of the rabab and contrasts it with the clear, ringing tone of the sarod. There are actually two schools of sarod playing – one in which the strings are stopped by the fingertips and the other in which the strings are stopped by the finger-nails of the left hand (as practised by Amjad Ali Khan). This is what makes the clear ringing sound and is one of the things that makes it so difficult to play. “These two nails I never cut,” says Amjad Ali Khan, showing the first and second fingers of his left hand. “They just get worn down. I have to file them after every concert. People might think I am just beautifying my nails, but it’s essential maintenance. They get little grooves cut into them from the strings.” I get a vivid picture in my mind of the ridges worn into wells in India by the continuous pulling of ropes. It is nails on steel that gives the sarod its clear, muscular sound. “In Hindi we say ‘Swara hi ishwar hay’ - ‘Sound is god’ and whilst you are playing you can feel god. I often have my eyes closed to feel the sound.”

Amjad Ali Khan shows how he can play melodies just using his left hand. “My father used to play like that for five minutes at a time,” he says. “Many years ago, a sarangi player at the court challenged my grandfather. ‘You must play anything that I can play’, he said. My grandfather took up the challenge and copied everything the sarangi player could bow on his instrument. Then my grandfather said: ‘Now you see if you can imitate me’ and asked the sarangi player to tie-up his right hand. My grandfather played beautiful melodies with one hand, but the sarangi player could do nothing without his bowing hand and lost.”

For Amjad Ali Khan the sarod is more than an instrument. He is more than a slave and it is more than a master. It is a friend and spiritual companion: “The sarod should have human expression. The sarod should sing, should yell, laugh, cry - all the emotions. Music has no religion in the same way flowers have no religion. Through music – and through this instrument - I feel connected with every religion and every human being – or every soul, I should say.”